Pluto

-

Posts

4,505 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

2

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Gallery

Blogs

Store

Posts posted by Pluto

-

-

There are two comparatively recent books on this subject.

Passenger Boats on Inland Waterways, D D Gladwin, Oakwood Press, 1979.

Swifts & Queens, A I Bowman, Auld Kirk Museum Publications No 9, 1984.

-

John MacNeill's 1833 paper on the resistance of boats in water should answer most questions, as will the attached paper.

-

The term 'flyboat' may have had different meanings, depending upon the canal. Generally, it suggests a general cargo boat which had priority at locks, and often working to some sort of timetable. Reliability, rather than speed, was important.

When it comes to speed, we are talking about 'packet boats', so-called because they were allowed to carry small packets, perhaps up to 56lb, as well as passengers. They usually operated in areas where there were long pounds and few locks. Considerable work was put into the design of the hull in the 1820s/30s, but the growth of rail traffic killed them off. The last on the L&LC worked between Burnley and Blackburn, but by 1840 it had become more of a pleasure boat, the owners claiming that as a mode of transport, the bar could be open throughout the trip.

-

They tended to be promoted by those with colliery interests looking to enter the lucrative London market.

-

Europe's first summit level canal was the Stecknitzfahrt, joining the Elbe with the Baltic and opened in 1398. It is possible some of Britain's important northern Europe trade used the canal to avoid the excessive Danish charges for using the sea route passing Copenhagen. The Chinese built their first proper summit level on the Grand Canal around the same time after the Yellow River's exit to the sea had moved from the north of the Shandong peninsula to the south, around 500 miles.

-

Work starts circa 1760,

1762 Batty Cut to be extended to above Hall Mill Dam; Ledgard Mill Cut to be lengthened

1764 Brindley becomes engineer; navigation opened up to Brighouse

1765 Brindley proposes extension to Sowerby; shoal dredged at Brooksmouth and canal completed to there.

1767 First flood damages, but quickly reopened to Salterhebble

1768 Second closure because of floods

1769 Open to Salterhebble

1770 Brighouse Old Cut, breaking of the banks; reopen to Sowerby

1776 Cut from Ledgard Bridge to Shepley Bridge opens and old Mirfield lock abandoned

1780 Bradley New Cut, Brighouse New Cut and Kirklees Cut to be built

1783 Brooksmouth locks altered

1785 Batty Cut extended

1791 Broad Cut to be surveyed; new Cooper Bridge Cut to be made

1797 Thornhill Cut from Horbury Bridge to Hostingley Lane to be built, replacing Dewsbury Cut

1805 Brighouse Cut extended to Freeman’s Mill

1812 Fall Ing Cut opened

1815 Elland Cut extended to Sowerby Cut

1822 Two locks at Brighouse instead of one

1823 Broad Cut extended

1828 Halifax branch opens

1835-8 Horbury New Cut, Broad Cut to Figure of Three, new lock at Thornes

1842 Kirklees Upper Lock to be lengthened

1861 Dewsbury arm sold to Lord Savile

1867 Batty Lock and Ledgard Bridge flood lock altered

1878 A&CN buy Dewsbury arm

1883 Fall Ing lock enlarged and one at Thornes lengthened; Broad Cut lower lock lengthened

-

14 hours ago, David Mack said:

It was listed in 1987, so one would presume that the listing description would match its condition at the time, and was simply never updated when the deck was replaced.

Listings should not be relied upon for accuracy. I have been trying to get those covering the warehouses at Wigan corrected for over thirty years. I also wrote a report on one of the Goole swing bridges where the listing appeared to be more about the bridge which was replaced around 1910 than for the one I was looking at.

-

Two reasons for more connections to lateral rivers in mainland Europe. Firstly, there are a greater number of large rivers used as waterways, and secondly there was a much greater use of smaller rivers as navigations. Researching 18th century navigations around the Rhine brought up a number of rivers used by boats capable of carrying just a few tons.

-

1

1

-

-

The pier abutments look like they have had a major rebuild, with the face walls completely reconstructed, not entirely unexpected on surfaces exposed to river flow. The drawing, preserved in the Austrian State Archives, seems to have been the work of Clowes, and shows the Dove Aqueduct. It was given to Sebastian Maillard on his 1795 visit to England, and suggests he may have met Clowes.

-

Some details here re women on board in the 1840s:

From: The Morning Chronicle, Dec 13th 1849

Labour and the Poor; The Manufacturing districts, Leeds

I should devote a few words to the life and toil of the men, who, before the era of railroads, were chiefly concerned in the conveyance of heavy goods from place to place, and who still transport by water-carriage a very considerable portion of our manufactured and mineral wealth - I mean the bargemen engaged in navigating our inland canals. … The boats are long and narrow, and deeply laden. A tarpaulin covers the cargo stowed amidships, and sometimes in the bow, sometimes in the stern, sometimes in both bow and stern rise one or two funnels, the number being according to the size of the boat, smoking cheerily, and proclaiming that the cabins of captain and crew lie beneath. As a general rule, a single horse draws these boats along, the driver being frequently seated complacently upon its back, with both feet towards the water. This individual belongs to a class often talked of but seldom seen. In the slang of the canals he is called the Horse Marine. The marine is, indeed his regular trade appellation. Sometimes a man or a couple of men, lounge idly on the barge’s deck, occasionally a woman taking a trick at the helm is the only person visible.

Let us descend into the after cabin of one of the larger class of barges, one carrying from 40-50 tons. It is a hot, choky, little box, between 4 and 5 ft high, near the scuttle is a stove. On either side run berths made after the usual fashion afloat. One is generally constructed broad enough to contain a couple of persons, the other often only room for one. Beneath them are lockers which serve for seats, and at the stern, just forward of the rudder opens the little cupboard, wherein the, sea-stock is deposited. Even with the scuttle open you will often find the air close and oppressive, but the captain will generally tell you that two, some three people sleep there with the hatch on. ‘We move it so as to make a chink, if we feel it over hot.’

The larger boats are normally navigated by a captain and two mates, and helped, of course by the marine. The average wages of the captain amounts to about 22s, those of the mates and marine to 18s weekly. The captain has often his wife on board, but sometimes one of the mates gives his missus a trip, the skipper on these occasions gallantly giving up the use of the cabin and sleeping with the other mate in the forecastle. Only one lady, however, is allowed to be on board at a time. The usual speed of the barge is from 2-3miles and a half an hour. The fly barges, which are commonly the larger sort, proceed night and day, never stopping, except at the locks, and to deliver goods.

Each horse performs a stage of from 20 to 25 miles. The marine in charge of the relay knows when the barge will be up, ‘to an hour or two’, a latitude reminding one of the very old coaching days. The smaller barges have only a single horse, which goes the whole journey. These boats tie up at nights. The bargemen always sleep on board. The marine looks after his steed and sleeps ashore. There do not seem to be any regular watches on board these barges, as at sea. The turns of deputy depend upon the circumstances and varying arrangements. Three hours is reckoned a fair spell at the helm, and if there is a woman on board she always steers when the men are at their dinners. In passing a lock, however, all hands must be on deck, by day or night

-

2

2

-

-

52 minutes ago, magpie patrick said:

I note the video claims 1890s for the rolling bridge idea, but the Oxford Canal bridges roll, and the concept there is presumably a century older. This is just a huge Oxford Canal Bridge!

The Schertzer type rolling bridge was introduced towards the end of the 19th century, the large rolling section ensuring that the bridge deck did not interrupt the bridge hole when raised, the deck rolling clear of the passage. Materials and demand affected the design of dock swing bridges, with the moved from cast iron to wrought iron being necessary when the width of boats increased with the introduction of paddle steamers. For small canals, I always liked the old L&LC design which used two concave circular cast iron plates as the bearing, with a spigot to centralise the deck. The plates could crush most stones, making them easy to swing, but the increasing weight of road traffic resulted in cracked plates which could jam. Alas, none survive. The lift bridge at the BCLM was used as a children's swing prior to being moved to the museum. They would swing the counterbalance weights energetically, resulting in the support columns and drive shafting becoming bent. There are lots of problems to be overcome with opening bridges, and I would recommend trying to keel any design as simple as possible.

-

The second 'National Rally' in August 1955, with commercial and pleasure craft mingling at Skipton.Three of the commercial craft appear to be carrying wool as there was still a major traffic from Liverpool Docks to Stockbridge and Shipley. The one nearest the camera seems to be heavier loaded - wool was comparatively light - so could be carrying sugar from Tate & Lyles.

-

-

There were two 'Botany Bay' wharfs on the L&LC. The one at Armley was where the first loads of wool from Australia were said to be delivered, while that at Chorley was named because living in that area was just like being sent to Botany Bay.

-

I wrote a report on the listed bridges in Hull, which included New Cleveland Street Bridge over Sutton Drain, built 1902-1903. This is considered to be the second reinforced bridge in the UK. The L&LC did purchase a concrete mixer in 1909, with the engineer becoming a member of the Concrete Institute. The research produced few specific early bridges, with most records covering patents for various uses of the several systems suggested for reinforced concrete. As canals were considered old technology by this time, concrete bridges were less likely to be used on them, and those which were were probably local authority structures.

-

-

Historically, they were often used where subsidence had affected the angle at which gates were hung. They were fitted to most of Wigan lock gates at one time. Their use on locks where there was no subsidence does suggest that inexperienced workers have installed them, with incorrect fitting of the pins or poor balance from the beam. The angle of the quoin could also have been altered if the lock walls have been rebuilt.

-

1 hour ago, magpie patrick said:

But others don't have such a poetic name, with Ystalyfera one can almost hear the close harmony singing....

Back in 1972, I did descend Bingley 5-rise with the Hammond Sauce Brass Band playing on the footbridges, which is perhaps as evocative of local tradition. As we are discussing lime mortars, a few years ago I did get the choir I sang with to give a rendering of Beethoven's Ode to Joy both inside and out of the limekiln at Langcliffe on a European Industrial Heritage day.

-

1

1

-

-

Pozzolano from Italy was known as creating a waterproof mortar by the 18th century in the UK, but its cost resulted in John Smeaton's research into a British replacement for his construction of Eddystone Lighthouse, which was the start of the development of Portland cements. I have seen both pozzolano and Portland cements being suggested for the construction of canal structures, but they were expensive, and of course there was no easy way to carry bulk loads inland with ease until canals had been built. I have also seen Trass mentioned, a German type of pozzolano. There does seem to have been reasonable extensive knowledge of hydraulic limes, though their expense meant that they were unlikely to be used except for very specific purposes, and early canal engineers, to a great extent, had to rely upon locally-sourced materials. Lime kilns were often built on site, and they were certainly used during the construction of the Old Dock in Liverpool by Thomas Steers around 1710-15.

The layout of Ystalyfera aqueduct is fairly standard, and I have seen examples of other bridges and aqueducts with a weir at their downstream side. This ensured deep water around the base of the piers which reduced the chance of erosion. It also provided the shallows necessary for a ford downstream, should the canal follow the line of a road.

-

4 hours ago, Tonka said:

But lime mortar is designed to let the water vapour out and the house breath. It is when people repoint there houses with cement mortar that they start getting mould etc.

Then they get hoodwinked by the damp wally brigade telling them they need to have a damp proof course injected and the bottom 1 metre high inside bottom walls re-plastered with gypsum. Then they make it worse by putting vinyl emulsion paint on.

End result the house is worse off then when they started and their pockets are a lot lighter

You are quoting what we know about lime mortar today, and I would certainly agree with how conservation should be approached. However, my suggestions were based upon what they were likely to know in the 18th century. There is certainly some written documentation, but it is usually limited in scope and can be difficult to interpret. You could have a look at: 1780, B Higgins, Experiments and observations made with the view of improving the art of composing and applying calcaereous cements, which can be found as a download.

-

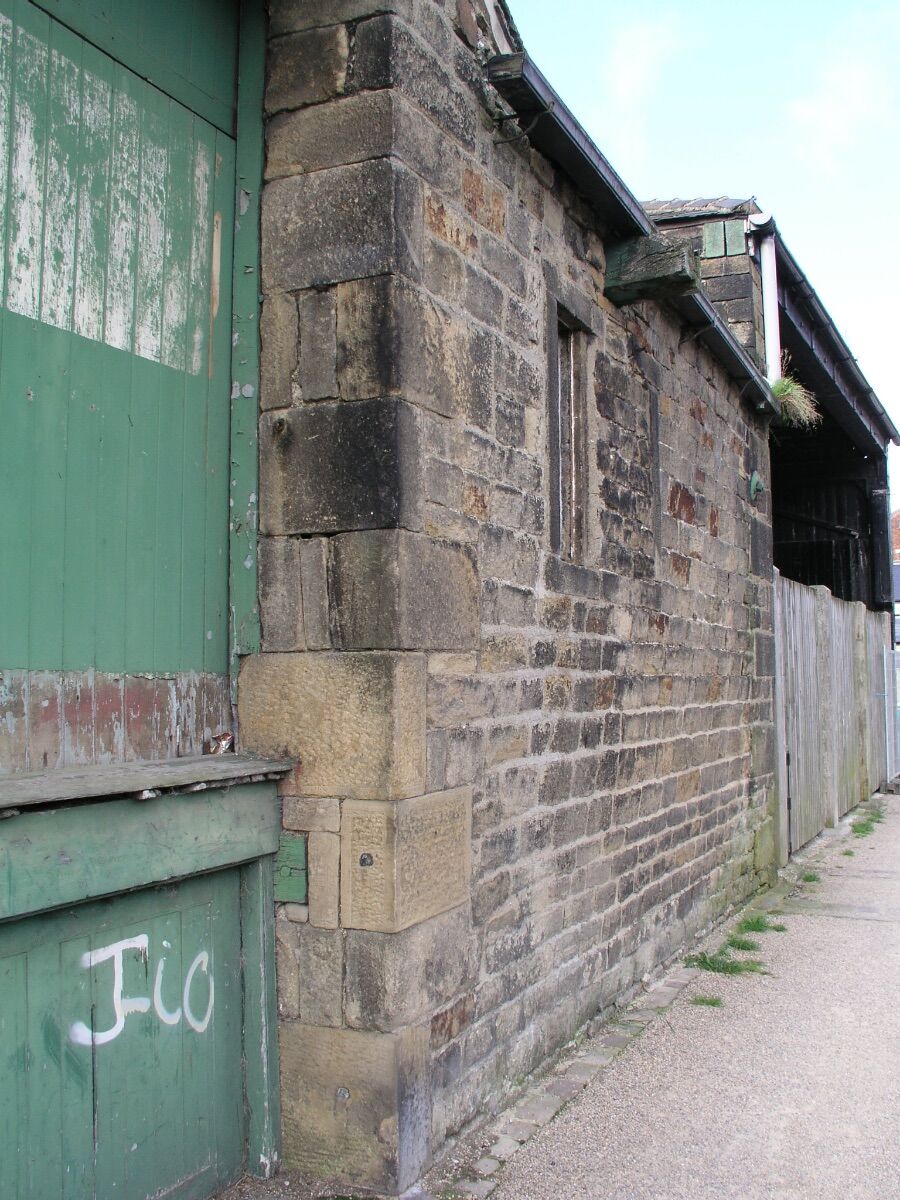

What I suspect the OP is looking at is how lime mortars were developed to become impervious to water and/or able to cure in wet conditions. Standard 18th century lime mortars were not impervious, which led Lancashire and Yorkshire builders to develop the water-shot wall, where the stonework bed dipped to the outside of the building. Rain water would then tend to run out of the building rather than in to it. This method usually dates a building to pre-1810/20, as after that it had become cheaper to buy or produce impervious types of mortar. The photo shows water-shot stonework used on Stockbridge warehouse, which was originally built in the 1770s.

-

Lime mortars are an interesting, but difficult, area for research as in England they are on the border between academic research and the knowledge gained by a craft training. English universities only looked at pure science and seemed uninterested in applied science, certainly related to civil and mechanical engineering. This was much less so on the continent, and to an extent in Scotland where both pure and applied sciences were studied. This is reflected in the more numerous engineering-related (and specifically on mortar) books published on the continent. In England the industrial revolution came about because of our craft tradition, with European countries keen for English craftsmen to cross the Channel as they were considered much superior to local craftsmen.

With regard to lime mortars, there are some English contemporary academic papers and archive material, though these could be the result of 'pure' scientific research, and not widely used in practice. From looking at archive papers related to those actually involved in canal construction, they would sometimes stipulated specific lime sources for mortar, though at the same time use locally-sourced lime products for less critical works. The percentage of each would vary from job to job depending on cost, time-scale and availability. Although poorly educated in modern terms, the craftsmen engineers who built our canals had a wide knowledge of lime mortars which had been passed down from craftsman to apprentice, and they often had specific demands for a particular type of lime. Rennie's notes in the National Library of Scotland contain a number of analyses of lime made as he travelled around the country. I would expect each engineer to have his own favourite compositions when it came to mortars.

-

42 minutes ago, David Mack said:

Not a branch, but a private colliery canal. There used to be a number of derelict boats in various stages of decline.

-

There was a paper on early Portland cement written by P E Halstead published by the Newcomen Society in 1961, with Skempton following the next year with a look at developments 1843-1887. I have also attached a file I put together very quickly in 2009 when the use of lime on the Augustowski Canal was proposed for World Heritage. You can find numerous contemporary books on the subject by a trawl through Google Books.

-

1

1

-

How fast did flyboats go?

in History & Heritage

Posted

A 1797 drawing of a Lancaster packet boat. RAIL 844/8/1