-

Posts

319 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Gallery

Blogs

Store

Everything posted by John Liley

-

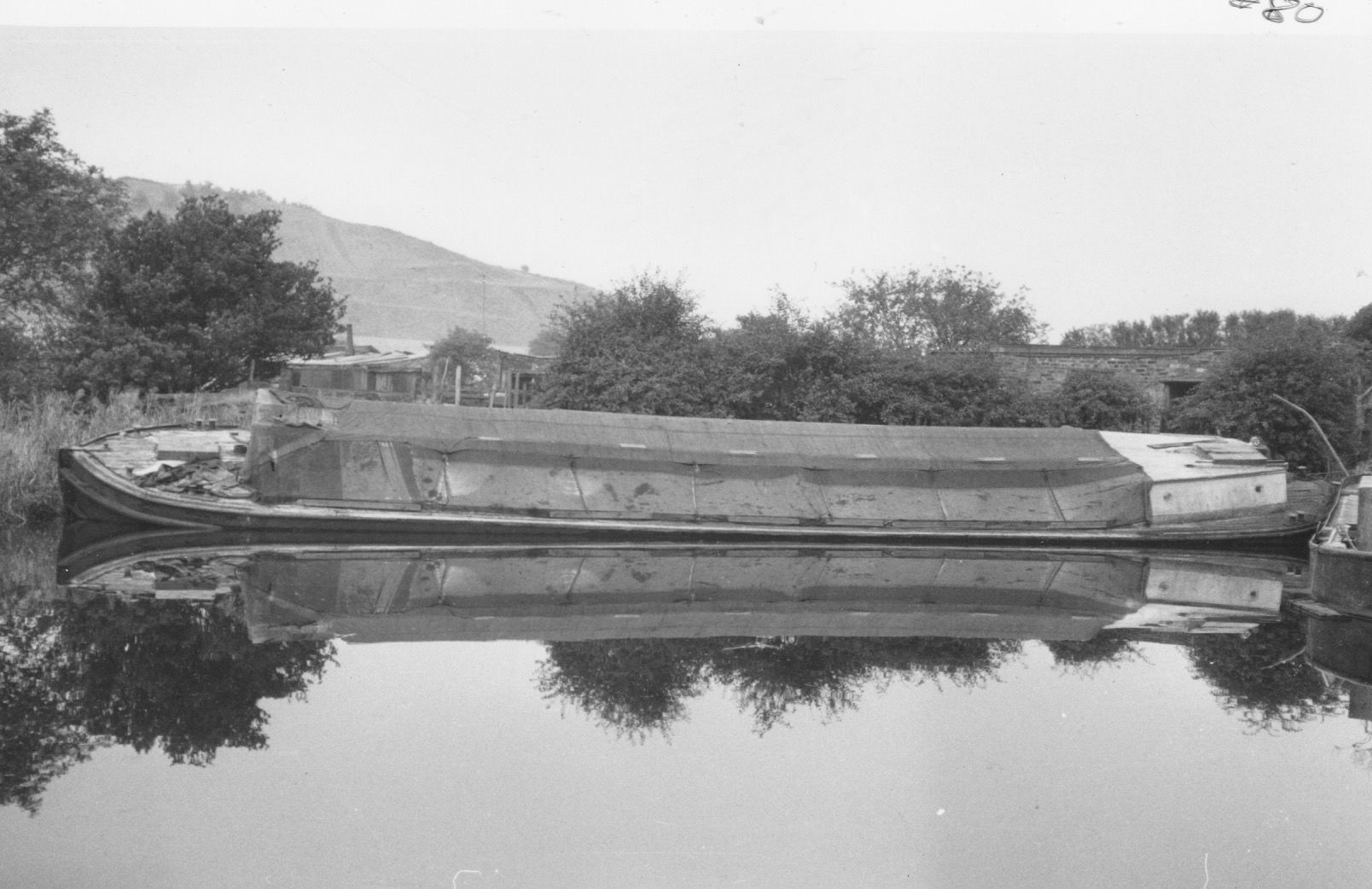

I seem to have travelled at times of decay. The collapsing factory was at Burnley, if I remember, the barge on the bank somewhere on the eastern side of the Leeds and Liverpool, the one heeling over at Wigan top, all in 1970 .To cheer things up a little the Richard is unloading newsprint at Leeds, a year or two earlier

-

I know the feeling - the message from VNF, the miles to cover (on the assumption you had nothing else to do). We have just, last night, Nov 28,had a call to say the Yonne water level has been dramatically dropped (in order that the Auxerre barrage could be repointed), that the gangplank structure has gone into the water, that the vessel is tilting, etc. Fortunately a family member is still in France, though on the way back to Blighty, and can turn around to sort. At least we don't have a lorry to recover.

-

The two restaurant berrichons failed to get certificates from the navigation authorities at Nevers, who, until then had always been to some degree understanding. Their reasonableness, however, had stretched in certain quarters, where the issue of navigation permits had been eased by gifts of whisky and brandy - in some quantity, I believe. . This was latched onto by the parallel authorities at Lyon and Paris, so Nevers appointed new brooms and put on a show of severity. Whether this was merited in the case of the berrichons I would not know, but I had a tough time with the same inspector myself when he made us make a 10 day voyage there and back just when we needed it least. He could easily have come to us in his car, which would also have saved us the all night sessions of work and the rushed exit from the dry-dock we were currently in. It did not help them in the end: the Nevers navigation commission was scrapped and Paris took over. We spend a lot of time now convincing them our barge is not a bateau-mouche and that the Nivernais differs from the Seine (Hence the regular replating of the hull bottom, owing to the things that we hit).Here, to cheer this account, is a picture of a deeper bit.

-

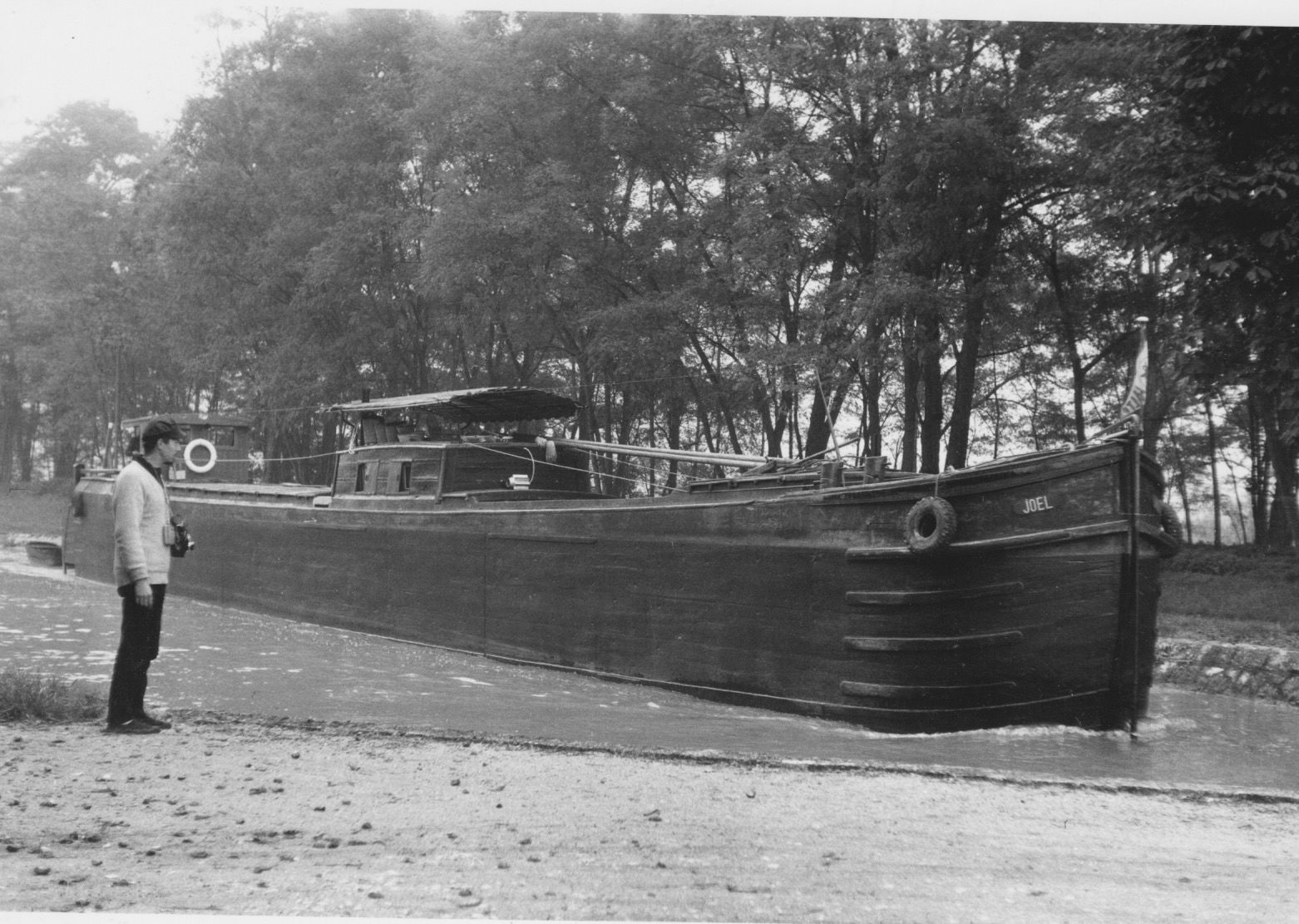

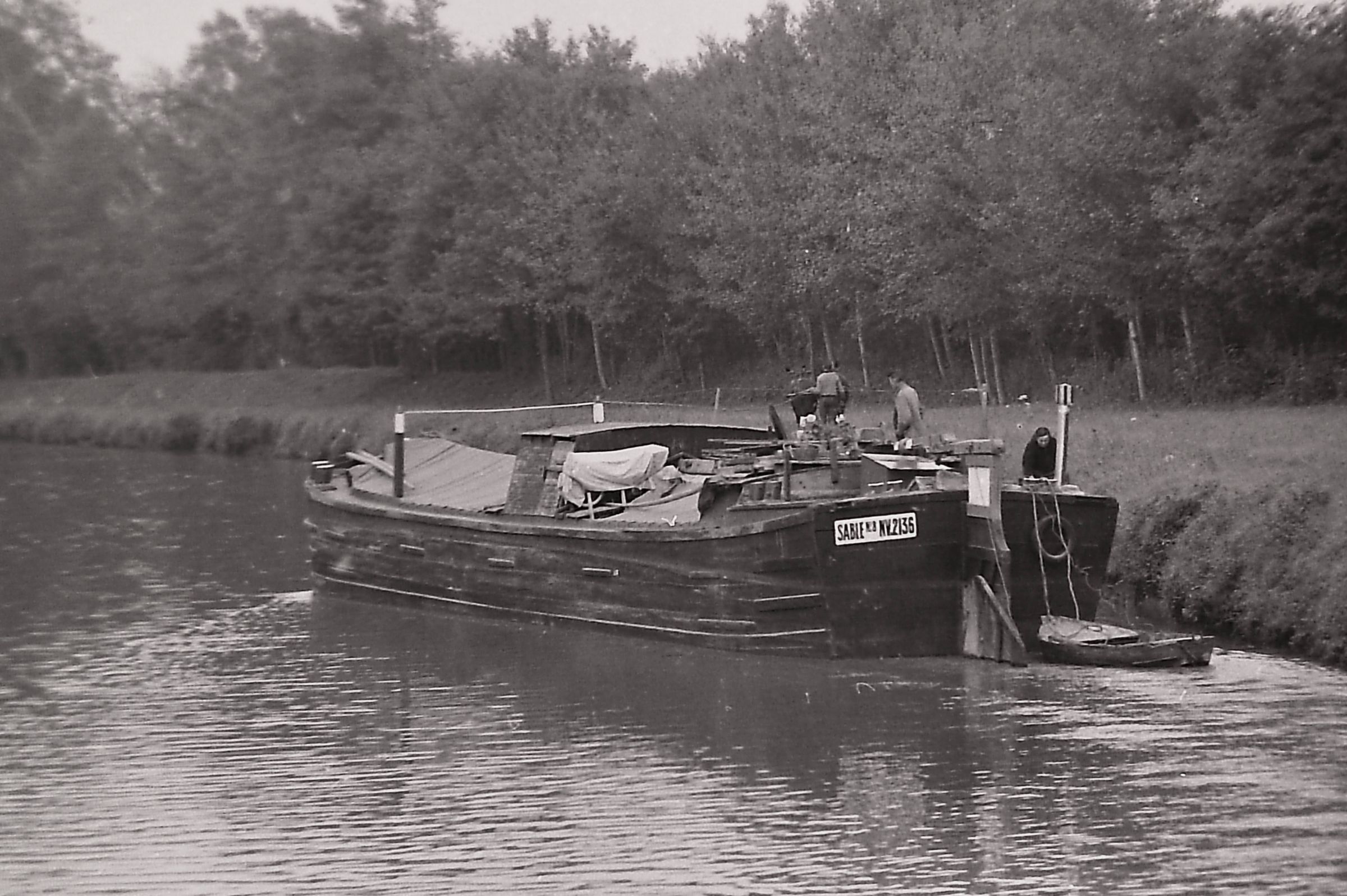

This berrichon came floating by during our trip of 1968. She was motorised and adapted for leisure use. Note the strings from the wheelhouse to the bow rudder, an arrangement beyond my personal understanding (We inherited a bow rudder on our later vessel Secunda and I never got the hang of it at all). Also seen on that trip were the railway sidings for the cement works at Beffes, next door to Marseilles-les-Aubigny. Ten years later, with Secunda as a hotel-barge, we were based beside these sidings, under the auspices of the hire-boat company Loire Line. Thinking it would be nice to have a bar for the Loire Line clients, Jim Clarke, the manager, pulled from the water one of the remaining wooden berrichons, which would otherwise be taken away for scrap. and sawed her in half to make the bar. It all ended badly as the only clients were the railway workers, who came in several times each day for a 'canon' as they were known, ie a tiny glass of vin ordinaire at the government-regulated price of, if I remember, 80 centimes in old money.

-

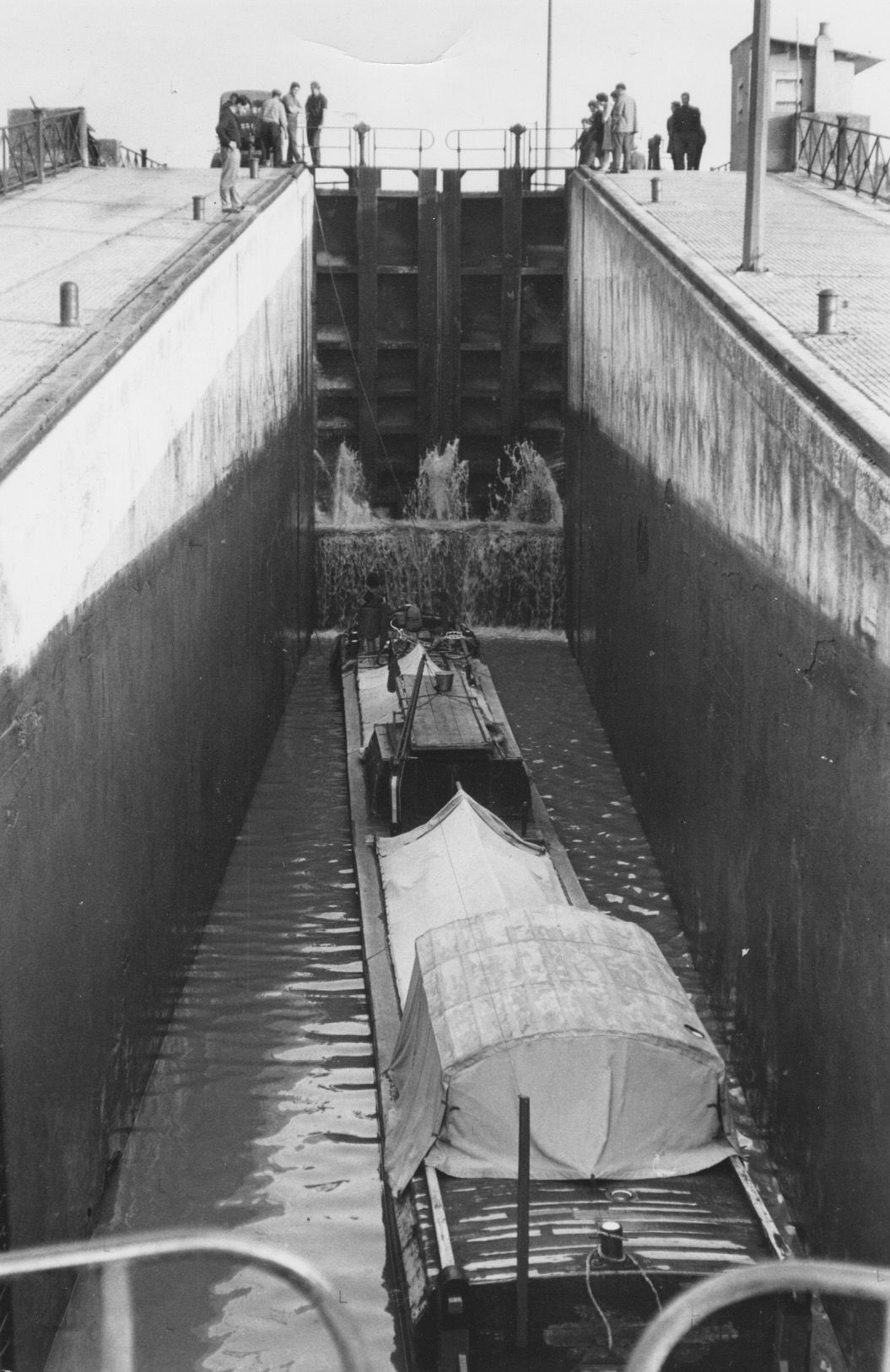

In summer, and at weekends, there is usually a bundle of onlookers at Le Guetin. If British people stare at you and you stare back they generally look embarrassed. In France they will wave: one of those cultural differences I find rather charming. They are just about to do so here, but I had to flick the ropes off - never easy in such deep locks as these - so I didn't have time for more photos.

-

So long ago, I hesitate to reveal it. 1968. I had just been made editor of Motor Boat & Yachting and was invited to the area by Peter Zivy, who was struggling to keep the Canal du Nivernais from being abandoned. He lent me one of his six cruisers for two weeks and, being intent on seeing as much as we could, we did the full circuit from the top of the Nivernais to the Seine and back. I wrote four articles on the trip, which Peter was able to wave in front of the government minister concerned as evidence of the enthusiasm for canals in the UK -Peter's firm was the only one in the whole of France hiring boats at that time. The concept for French people was a strange one and, anyway, they had to pass exams before taking out a boat. Visitors, on the other hand, could travel under whatever rules were in force in their home countries and, fortunately, in Britain there wern't any. Hence Peter's interest in a British clientele.. A couple more horse-bpat photos herewith, both in the vicinity of Le Guetin, near Nevers.

-

Whil sorting out the photo of the canalside distillery on the C de Garonne I came across further photos of the Sirdar, the last working berrichon (vessel from the Canal de Berry), the nearest thing in France to a narrow boat. Here she is working through the staircase locks at Le Guetin, on her way with a cargo of cement to a factory at Digoin. The horse and mule that towed her had to go by local road while a tractor pulled the vessel along the aqueduct over the Allier at the top

-

The slope, together with the one at Beziers, was an experiment on behalf of projected new waterways elsewhere, in particular. a jarge-sized link between the Rhine and Saone. But locks, apparently, are considered more reliable. On a separate note I fondly remember the Garonne Canal for a travelling distillery, encountered one day upon the banks. Such stills were common when I first started visiting France, supervised by genial gentlemen who would convert whatever might be brought to them into a high-percentage form of firewater. They were phased out by government decree, although such distillation continues, under licence, at many wine-makers, mainly to produce marc from grape remnants. It used to be possible to buy marc at greengrocer's shops, though that trade, too, seems to have faded.

-

A different kind of lift or, rather, a water slope, This one, at Montech on the Canal de Garonne, has been out of use for ten years, but is due for restoration, soon. A pool of water is pushed up the slope by the moving gate, propelled by the two locomotives. We brought the barge Palinurus through in it many yearsagao, and also travelled in the steeper one beside the staircase locks at Beziers on the Midi. The latter ran disastrously out of control one day, fortunately without a boat inside, although the wave it created wrecked another, a hire boat in the next lock down.

-

The glorious Mosel once again: the hill at Cochem, the path through the forest to Burg Eltz and the castle itself, owned by the same family since the 12th Century (33 generations) Roger Pilkington in his Small Boat series goes on at length about this castle, how it was never successfully attacked and how remote it is. When we got there we found it jam-packed with middle-aged German women, moving like battle-cruisers in the bar-room with giant jars of lager. It was strong stuff too. We only had one glass each, but the walk back was strange. And those woods are spooky

-

Thank you for this, which is really useful. And thank you to all who have responded - it certainly seems a topic of concern. I will pass on these comments to Bill Fisher and Terry Kemp of the Kennet & Avon Trust, who wrote the initial article in the 'September' issue of Waterways World (which curiously appeared in late July). Were C&RT to be sufficiently well-financed there is no good reason why it should not continue with wooden gates as before - except production ,seemingly, is not keeping up with the rate of gate decay. Add in also that Britain is running out of suitable trees, and the case for using steel opens up. Why not, perhaps, a system of modular steel gate frames, to which could be added timber trim - plus rubber, or plastic, which I have seen used in France? A worthwhile university project, methinks. My main reason for launching this topic here, however, was to learn if any way can be found to curb over-pedantic vetoes by Conservancy officials. That has yet to be revealed. Did they, as a point of interest, object to those hydraulic gate paddles that were tried for some years in British Waterways days?

-

I find myself involved with pressure to change the material with which lock gates are made. Oak gates last between 20 and 25 years. Steel ones, though marginally more expensive, last far,, far longer. The present replacement rate is not keeping up. So, given the parlous state of C&RT finances, moving to steel seems a no-brainer. Two worthy members of the Kennet & Avon Trust put the case for modular steel gates in a recent issue of 'Waterways World' and I have supported this, commenting that if the heritage issue emerges, the Canal du Midi in France makes a useful precedent. This canal started, long ago, with wooden gates throughout, but nowadays has them made of metal. The Canal du Midi was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996 and nobody seems to have noticed the difference. However ... A letter in the latest issue of Waterways World points out that 25 years ago a steel replacement pair of gates was rejected by the Daventry Conservation Officer. A Heritage Advisor I have spoken to tells me that this is an ambiguous matter, that some officers would say OK, and others No. Some kind of central directive would be of help here. Any ideas on how to achieve this? It may seem arcane, but, long term, our canal system will descend into more and more stoppages through lock gate collapse. And then, ultimately, closure.

-

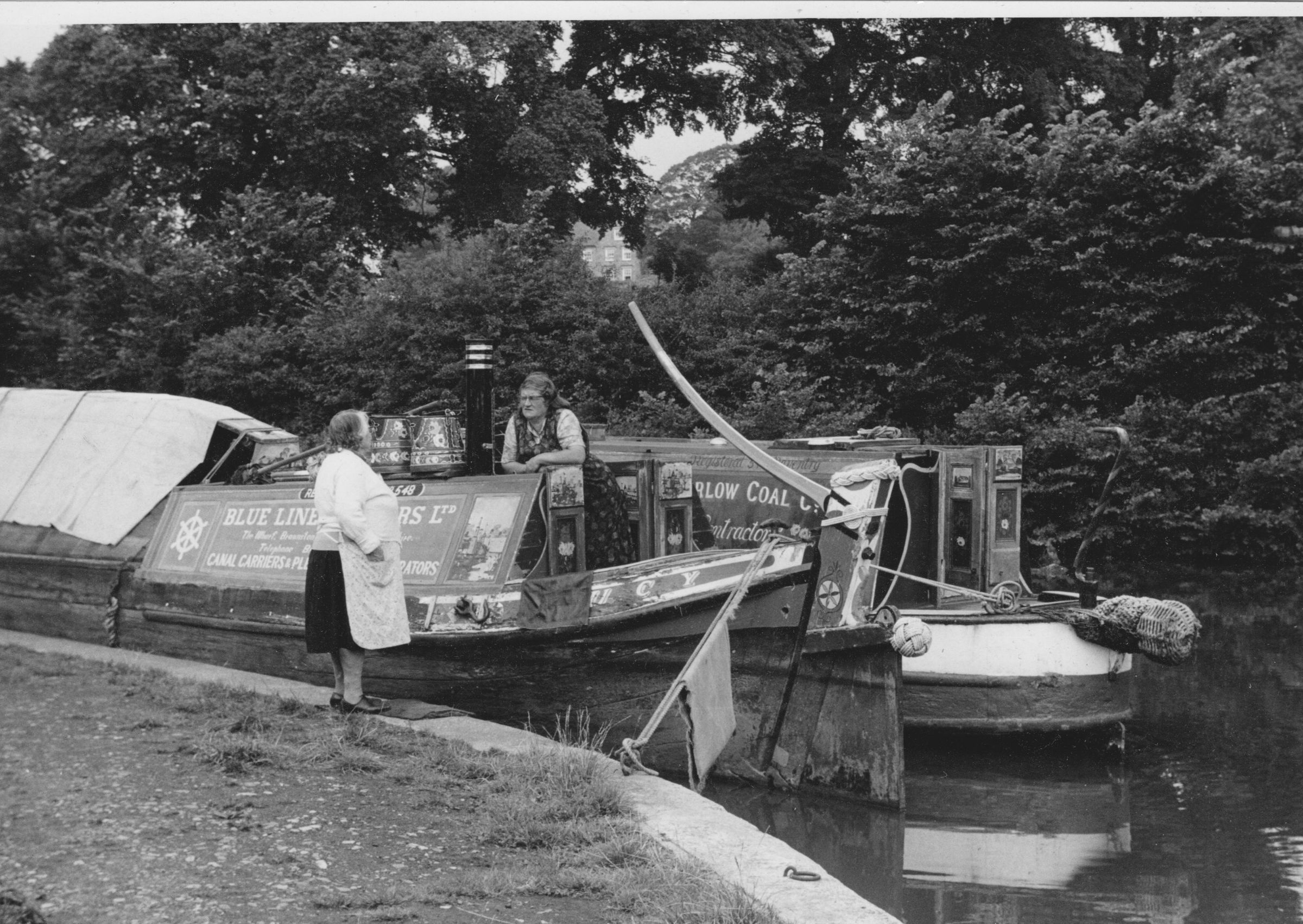

With Stanton and Belmont of the Blue Line fleet on the run from Atherstone to Southall many moons ago. In Buckby locks Jim Collins is seen putting into position the thumb lines, as I believe they are known, whereby the gates can be opened by pulling the boats back. Then, when the pair goes out the ropes unwind and drop down into the holds. We tried this on the Swan and all went well until one day the rope stuck and we came close to tearing the boat apart.

-

When our barge was in there, to lift her higher than the water level allowed they used to moor the freight barge you can see on the RH side of the top photo, stern-to against the gates, then run the motor flat out . The backwash from the propellor then did the job. Meanwhile a guy in diving gear shoved steel chairs beneath the hull. We were in there for a long spell and various other vessels came and went, since the dock could take two. Using the freight barge was an event they seemed to keep until late each Friday evening, when the entire staff would muster for the experience.

-

A French friend told me that when she was a child her family used to take holidays in this upper part of the valley here. Few other visitors came and there were wild flowers growing right across. Now the main autoroute from Paris to the south makes its way through. When the autoroute spur from Pouilly was proposed, it involved filling in the Canal de Bourgogne on the stretch nearer Dijon While there was still a fair amount of freight on the waterway then, leisure traffic was slight, so the lobby for retaining the canal was small. Somehow, though, it prevailed, and the spur was built alongside instead> Its presence on the approaches to Dijon explains why the hotel-barge operators in the region, who nowadays are many, turn their boats around some distance from the city.

-

This is the lock at Basseville on the Nivernais, one of the hardest to get into when the river is running. The barrage close by causes a sideways pull, so you have to head upstream on the approach, while drifting sideways. Just how much is hard to tell - until it is too late to put things right Fortunately we were OK this time, as the group at the lockside were student trainee keepers, expecting to see how it is done

-

The background to this boat is uncertain, though Robin Smithett in 'Precious Cargo - 50 years of Hotel Boats' tells us she was previously the Pauline, and very likely a Thames barge of that name, brought to the Norfolk Broads. There, between 1923 and 1929 she worked as a very early hotel-barge, . Originally 80 feet long, by the time British Waterways introduced her she had her square stern replaced with a rounded one and was shortened somewhat. Under BW's patronage "the waiters wore white jackets" and she was supposedly air-conditioned. Tantalisingly Robin Smithett also tells us "The boat was flooded at Whitsun in 1960 at Newark nether Lock, and in 1961 cruised to Boston" but gives no further details.