John Liley

Patron-

Posts

319 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Gallery

Blogs

Store

Everything posted by John Liley

-

From bitter experience I would never do this without some (responsible) person on the side-deck beside the hinge to ensure that the person on the pole safely completed his journey without (a) not having pushed off hard enough, (b) had pushed so hard so that his arrival was at ankle-damaging speed or (c) had fallen off on the way. I have seen all three. JL

-

When I viewed Secunda, and decided to purchase,she was very smart, with an equally smart dinghy. When I came to take her over the dinghy had been switched for a scruffy one with a dent in the side. The previous owners, meanwhile, had disappreared into the labyrinth †hat the Dutch system provides Still, it was useful on occasions (yes, there is rubbish in the Belgian canals too). Eventually, though, we found the dinghy too heavy and awkward, particularly near the Nivernais summit, where the 31 metre locks did not leave us room to dangle it from the crane at the stern. Plastic Sportyaks proved a better bet. The steel thing then was consigned to havimg flowers planted in it, for display in the port at Ayxerre.

-

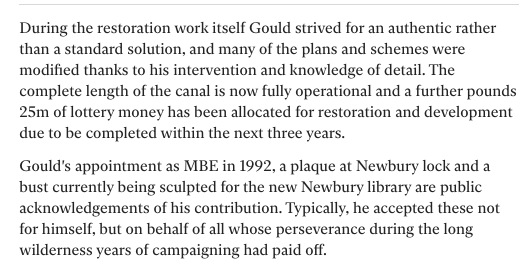

Going down the Yonne in Luciole we shared the journey with a two-barge combination, loaded with grain from Laroche-Migennes. Sometimes they left the lock first, sometimes we did. In the last photo the bow of the leading vessel is being carried to the non-towpath side by the eddies prevailing, but a touch on the wheel and turning on the power avoided a touch.

-

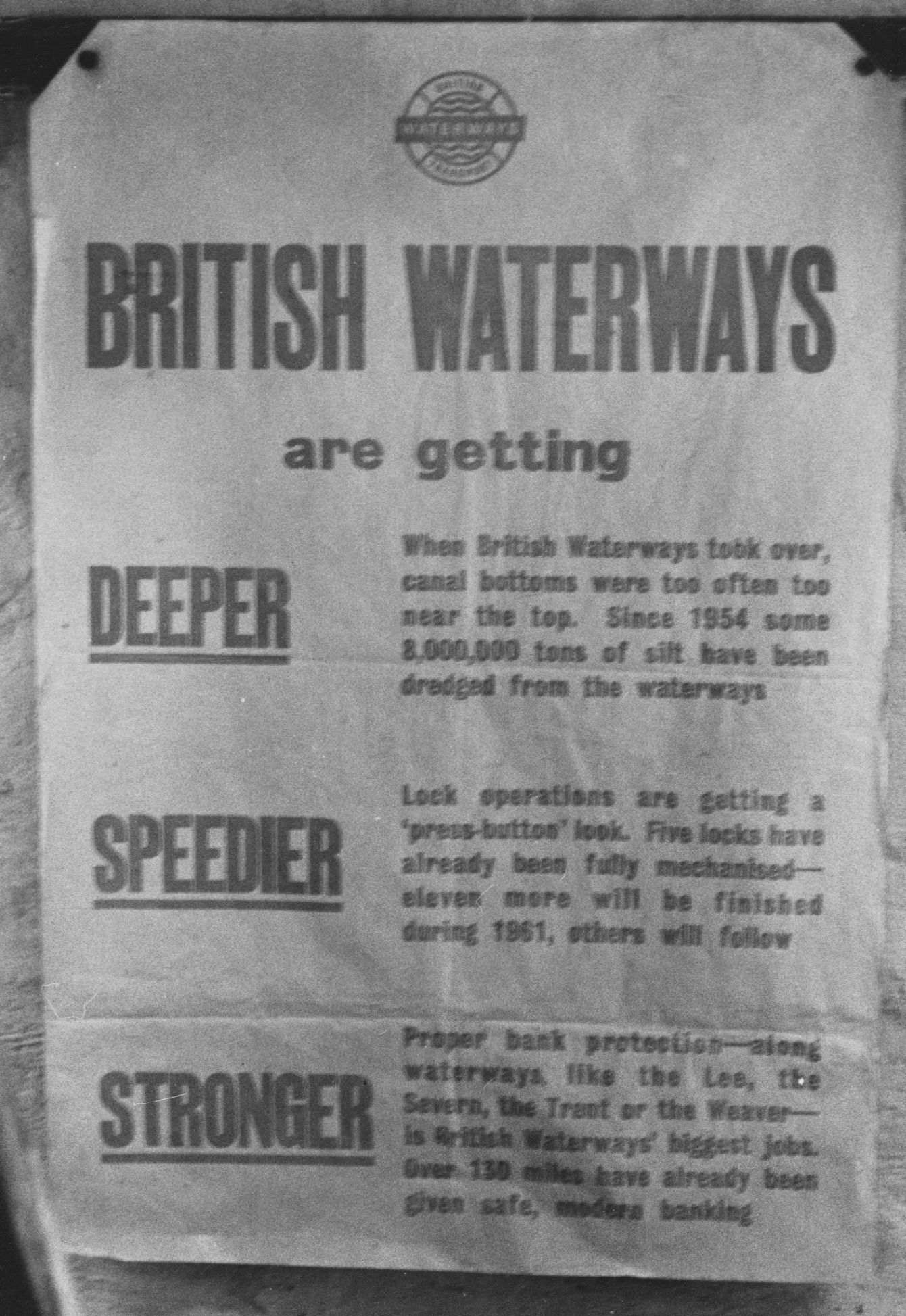

The last days of Willow Wren CTS. The company was formed to promote canal carrying in the expectation of government support for recommendations of enlargement of England's network - which never came. Here one of the last pairs carrying grain for Wellingborough is passing through Stoke Bruerne on the Grand Union Canal. Once at Wellingborough, they would have to wait with Whitworth's Miill just before them , it being the time of Whitworth's employees two-week holiday, so the boat crews need not have hurried up the GU after all. The third shot shows a Willow Wren pair loaded with tomato puree on an earlier traffic to Birmingham. The boats were rented from British Waterways when the latter gave up narrow boat carrying (with the exception of the lime juice traffic between Brentford and Hemel Hempstead)>

-

A view of the Nivernais summit cuttings in 1967 gives an indication of the unkempt state into which the canal had slipped. Human figures, bottom left, indicate the scale. When Secunda began operating 10 years later the future of the route was still unsure. The three tunnels at the top, so it turned out, when the canal was finally saved, were in urgent need of remedial attention.

-

Locks on the Nivernais are all still hand-winders, with a sprinkling of single-handed keepers covering several at a time. In high summer it gets better, with, part-timers recruited,. Often students, which works well. But if remote control takes over a valuable feature will be lost. Apologies for repeating a photo used earlier, but on the like of the upper Seine, where the operator sits in an office miles away, with fences all around and communication by radio, it is all too spooky for me. The house in the picture is unoccupied.

-

With mechanisation and the need to save on wages, lock-keepers are a threatened species in France. Their disappearance will be the visitor's loss. From the rich range of personalities encountered, three examples: On the Canal de l'Est, the Yonne, the southern Nivernais at Cercy-la-Tour. The last picture records my own introduction to waterways in France,. In 1967 Peter Zivy lent me a boat in exchange for a series of articles I would write extolling the delights of leisure cruising, then an unknown concept to those in the corridors of power. Peter's own company, deliberately sited at the summit of the Nivernais, had six boats only.and at that time was the only hire company on the inland waterways of France He lost a lot of money, but he saved the canal.

-

The Liason Dunkerque-Valenciennes is a large-scale waterway across northern France, upon which work started in 1959 when the existing peniche-sized routes were so crammed with traffic that a major enlargement was vital (The contrast with England is embarrassing to consider). Various reminders of earlier times survived for some time, including the barge lift near St-Omer and such as the lock-keeper's steel and glass hut, near Bethune.

-

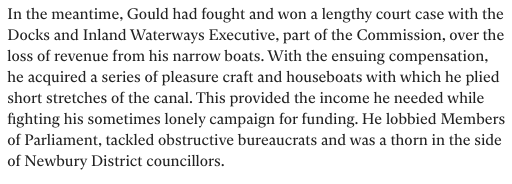

As I had sold theArthur back to Mike Streat, we parted company after the trip from France near these towers in the Thames Estuary. Mike wanted to get back to Braunston, where he had sold the business to Ladyline, but they were prepared to let him have some space. On the way he found himself and family fiddling their way through one of those un-statutory narrowings British Waterways tended to make. Apart from that the trip went fine. Secunda went on to Maldon in Essex, with plans to turn her into a hotel-barge. That's me in the window, wondering how the heck we were going to do it.

-

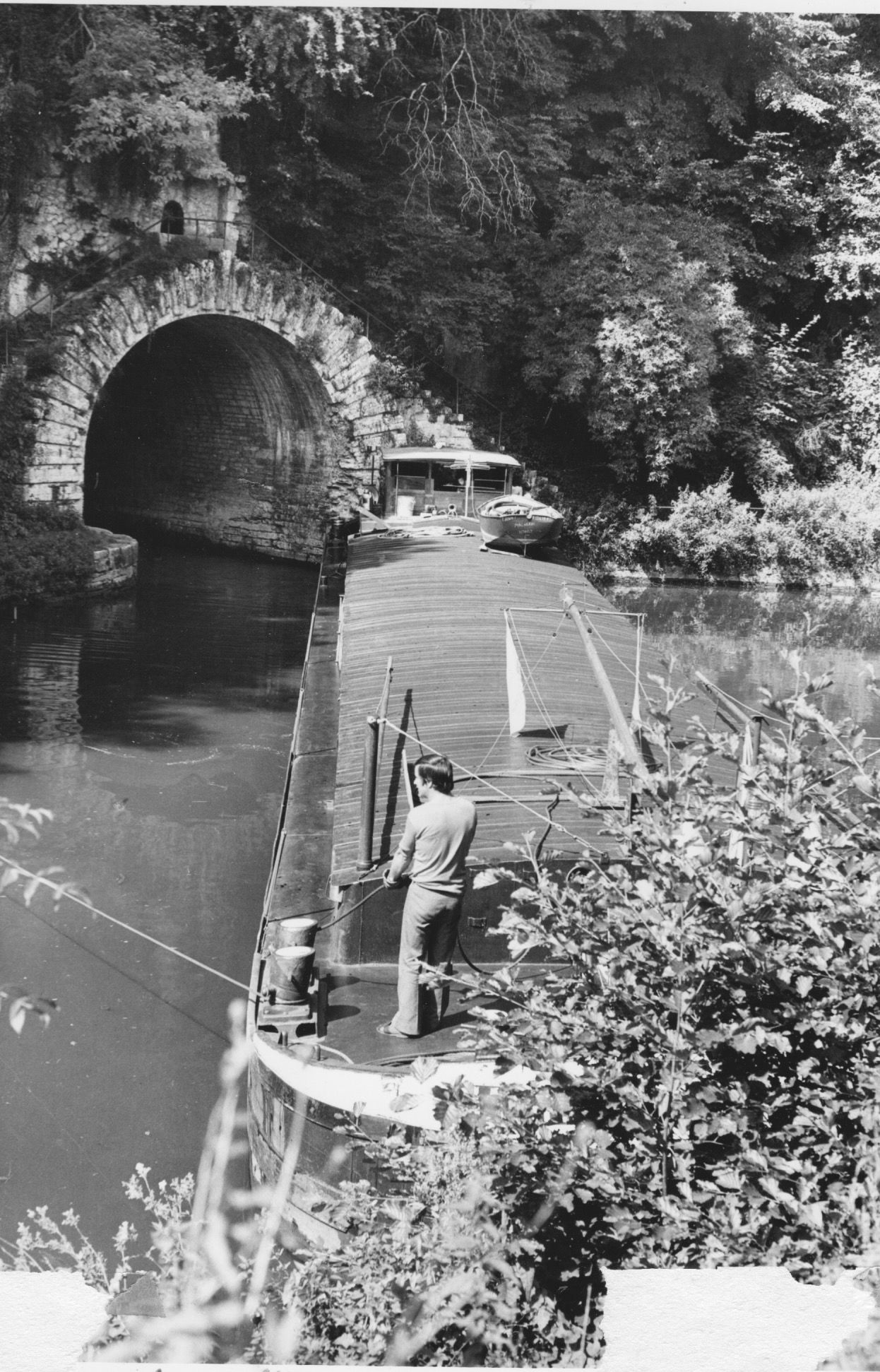

The Rhone-Rhine Canal again. This tunnel, the Souterrain de Thoraise, has since my photos, had a light sculpture installed above each entrance, with curtains of water to get through for those who are afloat. At an earlier lock, the loaded peniche, seen earlier, had to come out of the current at a lock entrance, approaching at minimal speed, then, once the bow touched, carefully motoring round, until straight. This is a dramatic waterway on the western side, but dangerous in in times of flood, with weirs to run alongside. There are also large rocks, with maps at the lockside, sometimes, to show where they are. The eastern end iwe found very different, with many locks and travelling keepers, with lots of sluice-winding to be done.

-

Two ways of turning a corner, on the Canal de l'Est,(southern portion) and the Rhone-Rhine Canal. The latter was scheduled in the 1970s for large-scale enlargement, a move with major economic consequences, but was cancelled by the French government in the face of local protest. Environmental concern, ironically, was the explanation given

-

Memory comes back to me. The ferry journey I described earlier, from 1960, was between Dover and Dunkerque. It persisted through the late 1970s at least. Air fares then were very high, so a common experience for back-packers and the like, returning to England, was to head for the spooky Gare du Nord in Paris, from which at 10 pm the boat train left for Dunkerque. Its make-up consisted of many carriages for those rich enough to have booked a sleeper, plus a further single one up front into which the rest of the us packed ourselves to a point at which the corridor seemed about to burst. The whole thing tootled along for a near-eternity before a laborious bit of shunting took place. The sleeping carriages were loaded on board while those in the single one were ejected , then made to walk to the ferry. A further long wait followed before the ship put to sea for her low-speed trundle to Dover.There a routine stopping train to London sat for a couple of hours or so, with the previous day's newspapers strewn around the floor. It was good for us, I suppose. Character building, and all that.

-

In 1960, or 61, I was a young shaver who worked for Peter Haward, who delivered yachts (by sea) for a living. We got a job to move a schooner from Naples to the Canary Islands and the start of it all were the train tickets we got for a late evening departure in sleeping cars from London (Victoria, I think) to Naples. I remember still the laborious shunting and shaking of our carriage onto a ferry at Dover (I think), the clanging of the buffers, the shouts and curses of the gentlemen who, beneath, us shackled us down securely once we were on the ship. There was a similar scenario at Calais, or maybe Boulogne (it was long, long ago).Then, just as we had got off to sleep again there was the arrival of further people to check our passports and ask complicated questions. On either side of the journey our trains were steam-hauled, not by gleaming locomotives as are seen on preserved routes nowadays, but by filthy ones, leaking steam in the wrong places and inclined to run, not just late, but extremely late.. Coming back from the Canaries, we took a ferry to Cadiz, then got arrested on the train finto Madrid for not having visas. The yachting voyage itself was comparatively straightforward.